“Visual storytelling of one kind or another has been

around since cavemen were drawing

on the walls.” – Frank Darabont

How can architecture serve as a catalyst for storytelling? How can architecture tell the appropriate stories?

Throughout time, people have used visual devices to capture stories. Visual storytelling displays a history of the past, an identity for the present, and a story for the future to compare and appreciate. Architecture is an ever-present form of visual storytelling. The built environment has the ability to capture the history of a place and tell that story through space. Architecture forms a visual, spatial link between the past, present, and future, becoming a point in the timeline of a place and culture.

Architecture constantly tells stories, but often these narratives are one-dimensional, ‘flat’ representations. These stories comprise a single layer – style – a layer that tells nothing of culture, history, or pride in a place, but is instead rooted in economics and the desire to build things cheaply and quickly.

In order for visual storytelling to occur in the form of architecture, a multiple-layered language must be developed. A spatial language is needed to tell the story of a particular place. If a spatial language is developed, it is possible to tell the appropriate stories – stories of the people who inhabit or have inhabited a place, the cultural history of a site, and evolution of use, building materials, and technology.

In order for buildings to tell the appropriate stories, ‘accommodating architecture’ must be created, that is, architecture that engages with the history of a site, respects existing conditions of a place, relates to present needs, and provides the potential for future use and adaptation

Here the design invites the users and visitors to touch and explore the story, it is possible to create new architecture to enhance the sense of being part of the story, and thus part of the past, present, and future.

For instance ,

A cultural arts centre with an emphasis on music is a program type deeply rooted in the production of ideas. Such a centre would encourage users to be immersed in the story of the South Waterfront and in the story of music. This program type would foster a sense of community, a sense of place, and engage with existing building and landscape elements through interior / exterior performance and display spaces.

And

A music centre encourages the idea of storytelling. Music is something quite magical that is produced and felt for a few moments in time, but can be remembered for a lifetime. It is ever-changing, ever-evolving, ever-inspiring. With a cultural music centre, spaces can be created that tell this story of music, that capture the feeling and magic of music even when it is not being produced. Vacant spaces should capture memory and excitement of music, so that visitors feel like sound is always present and therefore feel and understand the story of the place. In this sense, architecture acts as a vessel to ‘hold’ the story. New design does not compete with existing conditions, but instead enhances them. They should possess a humble, informal quality that encourages a dialogue between old and new, between people and music.

Translating the concept of storytelling into form involves a spatial language that reveres the past, fits present needs, and is adaptable to future use. The story of the site is always evolving, always growing, always changing. Likewise, the spaces that are created need to be able to grow and change to relate to conditions of the area. The form of the building constantly mediates between musician and music, between music and the community. Possible approaches to form include the creation of an outdoor space that serves as the ‘bridge’ between new and old architecture, between teacher and student, between visitor and music. In this sense, the outdoor performance space becomes the platform for exploring the story of music and the site.

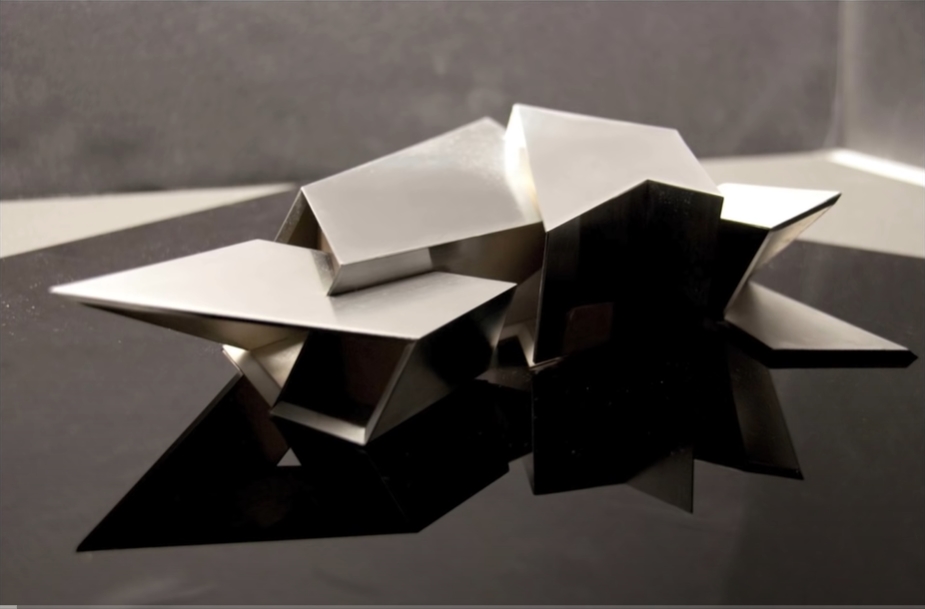

Another approach to form is the creation of layered spaces and planes – and thus the creation of a layered story. In this way, users and visitors would catch glimpses of other activities and functions relative to the production of music. The new architecture could also act as a frame for viewing existing elements of the site. One is aware of the space inhabited, as well as how that space interacts with others and thus other 1 layer of the story.

Article by S.S.Abishek , Creative head , Saran Architects.

References

Ambasz, Emilio. Progressive Architecture. Scarpa Reinhold Publish.ing, May 1981. pp 117-123.

Burns, Carol J. “On Site: Architectural Preoccupations.” New York: Princeton Architectural Press, Inc., 1991.

Byard, Paul Spencer. The Architecture of Additions. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1998. pp 57-60.

Fentress, Curtis W. Civic Builders. Great Britain: Wiley Academy, 2002. pp 155-159.

“Knoxville South Waterfront: Creating an Actionable and Inspirational Vision” (revised November 7, 2006)

Trencher, Michael. The Alvat Aalto Guide. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996. pp 152-154.

“Two Architects Ten Questions on Program” (answers by Rem Koolhaas and Bernard Tschumi; questions by Amanda Reeser Lawrence, Ana Miljacki, and Ashley Schafer)

“Zoning Ordinance for Knoxville Tennessee” (revised October 24,2006)

Zumthor, Peter. Peter Zumthor Works. Lars Muller Publishers, 1979-1997.